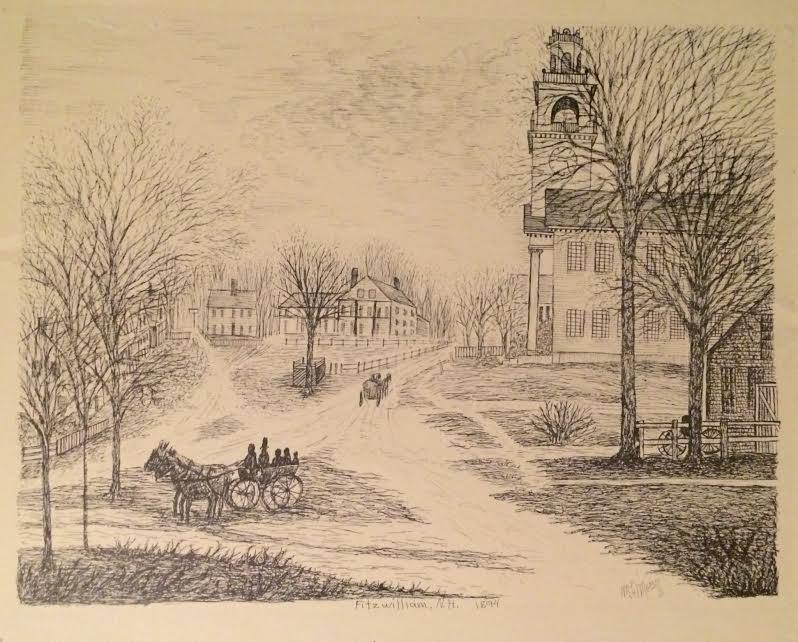

A Brief History Of Fitzwilliam

The town of Fitzwilliam was named by the colonial governor, John Wentworth, in compliment to his kinsman, the Earl of Fitzwilliam of England and Ireland, and given its royal charter by George III in 1765. In stately phrase it is granted “by the advice of our trusty and well-beloved John Wentworth, Esq., Governor, and hereby declared to be a Town Corporate by the name of Fitzwilliam, and to have Continuance forever.”

The town was organized by a group of men in Massachusetts who had bought the rights from the original holders of the Masonian Grants, and the region was known as Monadnock No.4. It was six miles square, and the land was laid out in lots of 100 acres each, those set aside for the meeting house and the minister’s house being in the exact center. By the terms of the royal charter, the grantees were expected to build fifty houses, “each with one room at least 16 feet square,” and within five years to build a meeting house and “to have constant preaching there.” There were two other conditions in the charter. The lots were to be sold “to such Persons as would engage to settle and improve the same,” and “All the White Pine Trees are Reserved for the Use of the Royal Navy.”

But as early as 1762 the pioneering spirit of the age had brought the first settler. Benjamin Bigelow and his wife Elizabeth had made their perilous way from Lunenburg, Mass., into the wilderness which was Fitzwilliam, and on May 10, 1762, began the town’s story with the birth of their baby, under the shelter of the oxcart which had brought them thither, and which, tipped up against a tree, was their first home.

It took determination and hardiness to come to Fitzwilliam in those days. Most of the pioneers were from the comparatively settled regions of central Massachusetts, and here was primeval forest. There were only two roads, one the military road, dating back to French and Indian war days, which came in from the south and crossed the town in a roughly diagonal line, and the other the “Great Road,” along the easterly line of the town, now known as the Fullam Hill Road.

At first, the settlers came in slowly. In 1767, five years after the Bigelow family came, the total population was only ninety people. Elizabeth Bigelow used to say in her old age that for years she was the handsomest woman in town, because she was the only one. It was not until 1770 that there were enough people settled here for them “to provide Stuf,” and set about building a meeting house. According to New England tradition, it was built on a hill. It was a plain, square building, with the burying ground adjacent. It must have stood where the present road now passes the burying ground, and no trace of it remains, though the ancient grave-stones of the men who built it, and the monument of its first minister, are still there. The first schoolhouse stood opposite, near the present school. The meeting house was the center of the town, not only geographically but in importance, the one place where the people could get together from their far-scattered clearings for worship, town meetings, and as Revolutionary days came, to have their war meetings.

The first inn was built by James Reed, the only one of the original proprietors to live here. It was the first framed building in town and was two stories high. It stood near the route of the old military road to the north, on what is now the Upper Troy Road. Most of the homes of the first settlers were built of logs, and of them no trace remains. The two oldest houses in the town today were both built in 177l. One, in the village, was built by Jonathan Locke, a notable example of its type, now the home of Mr. and Mrs. Francis C Massin; the other, on the Rindge Road, was built by Samuel Kendall, and is the home of Mr. and Mrs. Otis Rawding, and called “the most photographed house in town.” Its side door is the one out of which Mrs. Kendall stepped and came face to face with a bear, but “she shook her apron at him and he went back into the woods.”

By 1775 the population of the town had risen to 250 people. The houses were still scattered over a wide area, only a little of the land had been cleared and they had just established the town government; but with the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, patriotism rose above all other claims, and Arnold’s expedition against Canada, Bunker Hill, Bennington, Saratoga and Ticonderoga are names in Fitzwilliam’s history. Forty-three Revolutionary soldiers lie in the old burying ground on the hill.

By the beginning of the 19th century the town had sawmills, gristmills, tanneries, taverns, stores, twelve schools and a singing school. It had also the Rev. John Sabin, for forty years arbiter, and on occasion, autocrat. Of him, many stories survive. A visiting minister once asked him where the people got the stones for their miles of stone walls. Mr. Sabin said, “They get them off the surface of the ground.” And the guest exclaimed, “Why, it doesn’t look as if one had ever been picked up!”

Fitzwilliam was a busy place in those days. Five coach roads connected it with the outside world. While most of the men were farmers – it is an old story that on one occasion there were gathered on the Common 100 yoke of oxen – the women, besides spinning and weaving the materials for their clothes, braided palmleaf hats, a business so profitable that Mr. Sabin once commented drily, “The dress of the assemblies shows it.” Later on, woodenware was manufactured in such quantities that fifty travelling salesmen were employed. At one time Fitzwilliam was known as “The blueberry town of the world,” and in the season 100 bushels were shipped daily to Boston. The price was five cents a quart.

About the year 1840, the rocks of Fitzwilliam, which Mr. Sabin once said “were not very frightful when you were accustomed to them,” began to prove valuable economically, and the granite industry which arose then became the important business of the town. Fitzwilliam was one of the three principal granite centers of the state. The building of the Cheshire Railroad, in 1848, provided transportation, and the industry reached its peak from l9l5 to 1918, when it had brought in nearly 400 new residents as workmen and their families.

With the years came the gradual changes of a New England town – from farming to many small business enterprises, town improvement, cultural societies and the growth and influence of the churches. Fitzwilliam did its part in each of the six wars of the period, with its quotas of men, the Women’s Relief Corps, the Red Cross and Veterans’ Societies. The mid 20th century brought new industries and many young families, changing the picture of the town. With this young element has also come a new phase, for an increasing number of people find Fitzwilliam an ideal retirement place. The Rev. Mr. Sabin had a phrase for it, “We have a pleasant village, and so it strikes travellers who pass through it.”

The above is copyrighted material authored by Frank Bequaert and used by permission. Click to visit his site at www.fitzwilliam.org.